I’m trying to catch up on a lot of films that I missed in 2023, so I watched Asteroid City a couple days ago while doing some overtime comic page inking in on the couch. I’d heard a lot of big hubbub about it being The Best Wes Film In Years etc etc, but my ultimate prognosis was: it was fine? I guess?? I don’t know if I got as much out of it as others did, but that also might be a “me” problem.

Spoilers for Asteroid City to follow.

Visually, Asteroid City is a treat– the washed out reds, yellows and blues of the costumes and sets were lit by some of the prettiest outdoor lighting I’ve seen in a movie in a while. The scenes set at twilight, with a little breeze blowing in, were especially beautiful. I also appreciate a movie that’s unafraid to characterize its subjects through implication and offhand detail instead of just having them directly state “wow i’m FUCKED UP” or whatever. It’s an economy of narrative that I’m more used to seeing in comics– good comics, anyways– so it’s neat to see that approach taken to film. The soundtrack is the usual carefully crafted mixtape of period-accurate vibes. There were more jokes than I expected. (I think I forgot how goofy Anderson’s films can be? This is a significantly goofy film.)

I know I SHOULD like the metanarrative aspects of the film, as well. I understand that Wes was really pushing himself here, and I know that Asteroid City can be read as a commentary on his approach towards filmmaking in general. It’s just that, for a story that ultimately boils down to “fiction, even the fantastic kind, is necessary for understanding ourselves”– a sentiment I AGREE with, as a writer!– I feel like it just leaves too much on the table to make that point effectively.

Anderson and Roman Coppola’s oblique approach to character detail in this film’s script extends to basically EVERY detail of the setting. The film– or rather, the play within the film, which is shot more like a film than the film of the making of the play that frames it– is set in the American Southwest in 1955, and there are elements of this supremely whacked-out period of American history scattered throughout the film’s margins. Atom bombs are being tested nearby. Woodrow and the other smart kids are in town because of a scholarship awards ceremony run explicitly by the military industrial complex. The single Asian kid up for an award is treated notably worse than the white award recipients, and (probably not by coincidence), he’s a lot more politically active and anti-establishment. When an alien shows up to steal the town’s eponymous space rock, the army general serving as emcee floats the idea that it might be a Communist plot. The uncomfortable context of the play’s events never stops chafing with its precociously twee presentation, or its screwball sense of humor. These details are presented to us, but they have barely any impact on the story, and they’re not elaborated on, and hey, the whole play’s fake, right, so why even care?

Likewise, in the black and white “making-of” part of the film, we see that Asteroid City’s playwright Conrad Earp may be romantically entwined with its lead actor. (We get one single stage kiss, filmed from a distance. And that’s it for the rest of the film, baby! Gay rights!) I was really interested to see how a loner playwright and closeted homosexual working in the 1950s would feel about creating and staging a play that navigated so close to cultural critique. Asteroid City, the PLAY, is (on one level) about a disparate group of people, trapped in a deserted town by the government, choosing to believe that an alien Other doesn’t mean any harm and is worth celebrating, and going apeshit when their government tells them they can’t leave. That feels relevant! It’s also interesting that the true stated purpose of the play is to lull its audience into a deep and tranquil sleep, something we don’t see happen, explained, or even alluded to in the play’s plot. (It’s meant to encourage a state of mind open to dreaming? It’s a commentary on magical realist writing? It’s about stories, innit?) But we don’t get into any of this, and we spend way more time during the making-of “documentary” following the play’s depressed, divorced director, played by an impressively betitted Adrien Brody. (You can really tell Wes wasn’t considering The Gay Perspective when making this because he put Brody in that undershirt the entire film and then expected us to pay attention to what was coming out of his mouth. C’mon, man! We’re only human!)

Speaking of romantic perspectives, I guess I’d feel remiss to not mention that there’s a romance subplot– or, more accurately, kind of a situational tryst– between the main photographer character Augie and starlet Mildred, who is constantly pretending like she’s miserable to “prepare for a role”. We see her actress is treated like dirt by Conrad in real life. Augie’s genius son Woodrow also starts up a relationship with a fellow award recipient who’s Mildred’s daughter, and who, I’ll be real, I can’t even remember the name of. She’s… mostly just there to make Woodrow seem like he’s grown a little bolder? I could tell you “Wes Anderson has a hard time writing female characters that aren’t just props for his leading men”, but like, that’s not a new observation about Wes, nor is it one unique to him.

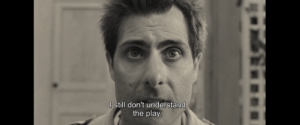

The biggest issue I have is that I wish this film had tugged on any of these threads a little more. There’s a weak attempt at catharsis with the pandemonium scene within the play, but the only point of actual emotional realness is Augie’s actor complaining to Adrien Brody’s tits that he doesn’t actually know what his character is doing or what the play is about. This is a very vivid and memorable scene– Jason Schwartzman staring dead into the camera with a pained expression, speaking frankly about feeling self-conscious and pained about his own confusion. In a film packed with stilted dialogue and awkward pauses, it really pops, and it’s the bit that most of my friends who’ve seen it mention as Their Favorite Scene.

But like, if this is a movie About That, about feeling lost as you try and make a work of art you don’t understand written by someone who you (might) be romantically entwined with, why not make more of the movie actually deal with that? Alternately, if you’re trying to make a movie about lacing a shlocky play with counterculture themes, why not focus on that? If you’re trying to make a movie about an emotionally detached father grappling with the loss of his wife, why not just make that movie (again)? Referencing all these plot threads in such an oblique way is impressively economical, sure, and it turns the movie into a big puzzle box for critically minded viewers smarter than my dumb ass to take apart, but ultimately this lack of specificity and the arm’s length that the metanarrative puts you at hampers any attempt for the film to make a clear thematic statement. (And no, films don’t HAVE to have those, but this is a film with a climax where everyone onscreen literally turns to you, the viewer, and essentially starts chanting “WE’RE MAKING A CLEAR THEMATIC STATEMENT”, so…) It feels weird when Wes has performed similar magic tricks to better, tighter effect in other films– The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and most notably The Grand Budapest Hotel. It’s also weird to see him try and pull a Charlie Kaufmann, when, let’s be real, not even Charlie Kaufmann can pull a Charlie Kaufmann that easily nowadays.

I do want to be clear here, I’m not a pro at film criticism, and I don’t know if I can still call myself a Wes Anderson Superfan or anything. I was HUGELY into him when I was an anxious, bookish adolescent quote-unquote “Boy” who owned multiple McSweeney’s anthologies, and owned nearly all of his films on DVD… but I haven’t seen Isle of Dogs or The French Dispatch, and I’m not really in a rush to do so these days. My favorite film of his is still Fantastic Mr. Fox, but that’s mostly because I love stop-motion animation and I’m a huge fucking furry. I can’t really see myself in his films anymore like I used to, I suppose, and that’s not endemic to him. This probably sounds blindingly obvious if you didn’t grow up a white middle-class “heterosexual” “boy”, but getting older and weirder has only made me more acutely aware of how narrow most media’s intended audience really is. Wes’s films are made for a specific group of people. I wanted to be in that group SO bad growing up. Now I’m not, and I don’t, so watching his films feels like visiting an extended relative who still only knows an earlier version of yourself.

ANYWAYS: I thought the story was kind of mid, but maybe that’s just my opinion and not an objective view. I’m glad I have so many friends who deeply enjoyed it. Also, again I was inking while watching this, so I was looking down at my comic page a lot instead of keeping my eyes glued to the screen, and maybe that fucked with the total presentation. Maybe I needed to see it in a theater or something. Finally, it’s worth mentioning that, despite all appearances, I’m just a silly little jester who falls over whenever I fart too hard, so don’t take anything I say about art especially seriously. Thanks for reading this anyway! You’re very cool for doing so! The blog post is over now.